The other day, my friend

told me that I’m “mysterious” on the internet because I’m not big on posting photos of myself on social media. My visage is so relatively rare that several people have asked if I have kids because basically the only two widely circulated photos of me feature my niece. I chalk most of this up to being grotesquely unphotogenic and, also, thinking that selfie promotion is gauche and vain.But that’s stupid. A lot of media parties or whatever I’ll go to, I’ll recognize a writer because they post their face on on Instagram but are only ambiently aware of the work they’re doing. There is this slight fame effect of posting for writers. People knowing what your face looks like provides a sense of notoriety outside of your actual practice, which is what influencers found out a decade ago and media orgs are apparently just figuring out right now.

Most of us desire some semblance of fame, or at least recognition for our work. It is, I think, very difficult to achieve that based on the back of output alone. Some individual writers figured this out a while back, and have gotten comfortable on camera, whether that’s just posting confessional Instagram stories or just doing a of selfies. But the institutional endorsement of that sort of thing is a more recent phenomenon.

This personal recognition economy is part of the “second pivot to video” that is happening across media right now. I now know what a lot of journalists look like, which, I would guess, was not something a lot of those journalists had in mind when they first started in the industry. It’s an inverted echo of the first pivot to video, which was also a guess as to what audiences wanted. But instead of numbers juiced by the Facebook algorithm that bamboozled media execs and destroyed a lot of careers, we’re seeing large news orgs take bets on turning their writers into personalities or, really, influencers.

I’m not here to say that YouTube or, to a lesser degree, Substack are existential risks to journalism as a practice; the industry is doing a great job of eating itself as it is. But I do think a lot of audience development types are deliberately trying to change what a reader’s understanding of a writer is as a way to elevate the brand of both the outlet and the writer in tandem.

There is risk there, of course. Turning a journalist into not only a household name but also a recognizable face only accelerates their risk of cashing out independently. I don’t think that’s bad per se, writers should be able to take their audiences with them and take care of themselves in the process. But I do wonder where it goes from here. You have media companies trying to reverse-engineer the influencer dynamic by putting their writers on camera. Suddenly everyone needs to be telegenic, everyone needs a personal brand, everyone needs to be building their platform. The Atlantic is putting reporters in front of cameras. The New York Times is encouraging writers to be more active on social media. The Wall Street Journal is pushing video content featuring their reporters' faces and personalities.

But this creates a tension that I don't think anyone has really figured out yet, or at least hasn’t been happening long enough for there to be a decent mode of understanding. What happens when a media institution successfully creates a media celebrity? Can they control how that person leverages their fame? And what happens when that person realizes they could make more money going solo? Where does that leave the relationship between institution and individual? It’s not as if writers needing to brand themselves is new1. Most of us have been trying to do that for the better part of a decade as we saw the media industry as we knew it start to crumble and fade. But where playing a character on Twitter or Tumblr felt at least discipline-adjacent, the influencerification of writers and journalists feels like a strange new frontier that not everyone is going to feel comfortable with.

There's also the question of what this does to journalism itself. When reporters become personalities, does that change how they report? When your face is your brand, do you start avoiding stories that might make you look bad? Do I need to start posting my face on the internet in order to become a successful journalist? Or is this just another dreary checkpoint in media’s blind march?

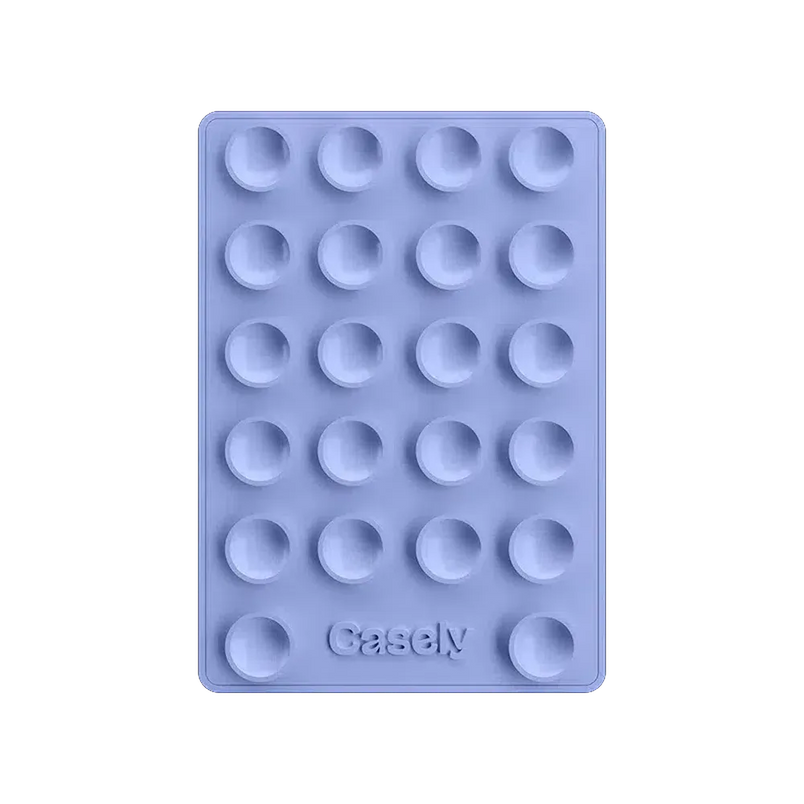

I thought about all these questions when, after talking with Max, I started looking at those little suction cup backings for your phone. Influencers use them to stick their phones to windows or mirrors to film OOTD or GRWM content. I found one I liked on Amazon; it was inconspicuous, a sort of entry-level model for the shy, would-be selfie video filmer. I have never been one to take pictures of myself, but, for the benefit of my career, I figured I had better get comfortable. An hour later, I canceled the order, still unsure about whether any of this really mattered at this point.

The smart outlets are probably going to start writing personality clauses into their contracts, the way TV networks do with hosts. But that's going to create its own problems. You can't really force someone to be charismatic or authentic.

This is great. Love the questions - ("When reporters become personalities, does that change how they report? When your face is your brand, do you start avoiding stories that might make you look bad") - I also think there's a sinister element in the journey to becoming a media personality in the first place. Right now, the fastest way to obtain the requisite attention and engagement to build influence is by being provocative. The algorithm, we are well-aware, does not reward thoughtful, nuanced, well-researched, and properly referenced analysis. It rewards ragebaiting.

As these established publications embrace the idea of incentivizing journalists to build personal followings, that means their 'success' may start being judged on social engagement KPIs in the same way brand social media managers are (rather than quality of reporting/writing). I'm sure this is already a thing via clickbait-y headlines etc., but adding talking heads exacerbates the situation. This will inevitably pressure them into more ragebaiting. So yes it will change how they report. And actually, rather than avoiding stories that make them look bad, it will encourage more problematic stories to provoke engagement, which further jeopardizes journalistic integrity.

This is something I think about a lot. I once ran a podcast that got quite a large following and I stepped away when the pressure to be a brand got to be too much. At the time it seemed like the right decision, but now I wonder if becoming a "brand" is inevitable.