The first time I wrote for the New York Times in 2018, my editor effectively balled up my draft and pitched it back in my face. I believe she used the term ‘unusable’ more than once, and told me that I would have to start from scratch and rewrite the entire thing. I was mortified because this felt like the biggest opportunity of my career. Writing about music for the paper of record. I must have sent that first draft to a dozen would-be mentors, got their blessings before I hit send. And it was shit.

Even after I refiled and the piece eventually got published, I figured that would be it for my career. Not good enough, not savvy enough, doesn’t understand what a story is.

The first time I wrote for the New Yorker in 2023, my lovely editor

wrote me one of the most remarkable notes I’ve ever received. I sent him 3000 words on an international fight about the origins of techno and he said that he ‘had basically no notes.’ I pitched a perfect game. An editor I deeply respected had looked at my work and found nothing wanting. The piece was published more or less as I had filed it.A lot happened in those intervening five years, and there are a lot of differences between writing for a newspaper and writing for a magazine. But I’d be lying if I said that I had worked on my craft deliberately between those two events. I was so despondent about what happened with the NYT that I basically gave up for a couple years, my career only revived by a piece about mixtapes and Fire Island and an editor that took huge risks to invest in me for reasons I still don’t understand but I am deeply, thoroughly grateful for. And for what it’s worth the New Yorker piece I wrote almost completely in a fugue-state, typing out a few thousand words in a single 6-hour sitting when I woke up at 1am after the piece’s structure, I shit you not, came to me in a dream and I rushed to go get it out of my head before it disappeared.

Most pieces exist between these two poles, and the concentration at one end or the other can tilt writers on their axis. We’ve all hit ruts, where your writing is foggy and drafts feel full of little chainlink fences that won’t let you connect ideas and sentences together. I am in such a rut now, and I chalk that up to good writing being an exhaustible resource. I think I have something like 13,000 words out in edits at different places right now, all written in the last 8 weeks. That volume may be where the returns on my work start diminishing. This is one reason I think it’s near-impossible to be a good weekly columnist. No one has that much to say every Wednesday.

In that spirit, it felt only appropriate that the first time I saw my name in the New Yorker’s fussy little serif, I also got an email from an editor I love working with that an essay I had filed was basically DOA. It wasn’t totally unexpected; I filed a bad draft that I struggled with the entire time I was writing. There was a disconnect between the ideas in my brain and the words my fingers were typing out. It was one of those situations where I should have raised my hand earlier and told him that we had a problem. We decided to kill the piece. It happens. C’est la mort.

So here’s where I’m doing a little experiment. I’m going to post this bad essay below. (It’s about sports replays and reviews being a scale model for tech dystopia so there’s a little bit of something in there for everyone!) I’ve edited it a bit between when I sent it to my editor and what you’re seeing now, but for the most part it’s intact. The reason I’m doing this is to illustrate how large the gap is, sometimes, between what a writer files and what you read.

Run the tape

The average NFL game lasts a little more than three hours, but for much of that time all you see is 22 guys standing around waiting for something to happen like a bunch of unusually large men waiting their turn at a deli. There is remarkably little action in a given game, about 12 minutes give or take. The rest is taken up by commercials, timeouts, and, increasingly, instant replays and reviews, which account for more air time than the live plays themselves.

Here’s one of my favorite examples of how that happens. In 2014, on a finger-and-toe numbing winter day in Green Bay the Dallas Cowboys were losing to the hometown Packers as the game wound down in the 4th quarter. With time running out, Cowboys quarterback Tony Romo lofted a pass down the left sideline where his star receiver Dez Bryant was running a "go route," effectively a bet that he could beat his assigned defender in a dead sprint. Romo bombed a beauty of a ball, all spiral and arc and airy physics, and Bryant snagged it with dextrous authority. The receiver’s feat was remarkable, one of those catches that exists at the intersection of talent and pressure and will have an infinite afterlife on highlight reels and broadcast B roll and YouTube compilations. But as Bryant tumbled to the ground, the ball popped loose and for a fateful moment, he lost control of it.

The ref went to the video booth and, after a short review, said that the stunning entry in the sport's history that millions of people had just seen had resulted in a "temporary loss of control.” Romo’s pass to Bryant took all of 7 seconds to happen while the review took almost 5 full minutes. The pass was incomplete. It was like the play never happened.

Dozens of professional leagues have introduced instant replay systems in recent years. Each other serves a different purpose: the MLB uses one to make out and safe calls; the NBA to challenge fouls and out of bounds decisions; the European soccer leagues for offsides, goals, and, in a phrase that can send fans into a fit, “fouls in the buildup.” These replays—slow-motion rewinds and exotic angles and on-screen annotations—have become the dominant way we watch sports. What happens live on the field of play seems secondary to the hyperreal slow-motion repetition, the image that contains not only the event but every bit of context and circumstance surrounding it. It’s a modern conundrum: we want as much information as possible even if it doesn’t teach us anything new.

The NFL has used the current replay system since 1999, though even through three decades of evolution they still haven’t figured out how to apply it to game-changing infractions like pass interference and holding penalties. The somewhat arbitrary use of all those super slow mo cameras have become a headache for fans; if you’re ever bored in Buffalo, ask a Bills diehard about some recent unreviewable interference calls that have broken against them and watch them combust. The Cowboys would go on to lose the Romo-Bryant game (known by bitter Cowboy fans as “Dez Caught It”) and the receiver’s fleeting lapse in ball security would result in the league's leadership getting together to change the rules about what "constitutes a catch" in order to retroactively confirm the call on the field, a sort of authority-bolstering retcon project. Ironically, a few years later the rules would be changed again and Bryant would have been spared some acrimony.

Despite all the headaches that reviews cause, we still watch. Seventy of the top 100 TV broadcasts in America were NFL games last year, a down period compared to 2023 when 93 of those places belonged to football games. (The dip was due to the Presidential election, which has taken more than a few cues from sports’ visual vernacular.) Speaking for myself, between the NFL season starting in September and the Super Bowl in February, I spent several entire Sundays in a darkened bar where my only real concern was whether my phone would die before I got into an argument about whether a given player was ‘elite’ or not and I needed to look up their stats to make a drunken point.

So what does one do when there’s only a few moments of action over the course of all those games? You spend a lot of time arguing over replays you’re watching. The debate over the Dez not-catch was hypnotizing when it happened. We stood in a bar arguing over every slight wobble and disputing the definition of possession like we were in a semantics seminar. You see the catch or the tackle or the juke and then you watch it again and again for different angles and perspectives and maybe even explicated on by a veteran and now-media trained player sitting in the booth. There is a post-structural sheen to watching what you just watched over and over again, as if the echo is more authentic and contains more depth than the original and reveals additional truths on each review.

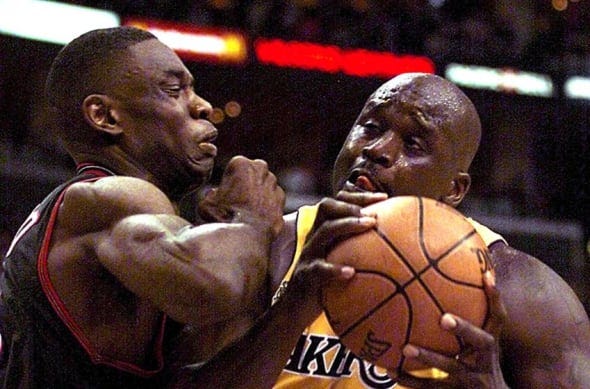

Video reviews were a way for leagues to correct past wrongs. I remember sitting on my couch as a 12-year old watching Shaq steamroll through Dikembe Mutumbo in the 2001 NBA Finals. Mutumbo was a mountain of a man, but Shaq was like a human in 3x zoom. Several times in the series, Shaq would receive the ball in the paint, raise his elbows just past shoulder height, and turn directly towards the basket, knifing his elbow into Mutumbo’s face in the process. If Shaq made those plays in today’s game, it would have been reviewed immediately and there’s a decent chance he would have been ejected.

Fans have always complained about fairness, about wanting the right calls to be made. A referee’s fallibility is something that unites rivals against a common enemy. So when video reviews came around, there was the implicit promise that all that was about to become ancient history. The correct outcome was going to become all but guaranteed now that we had the right cameras and technology. But people soon learned that videotape can lie too, and that applying technocratic rigor to something as subjective as an advantage in sports can lead to frustrating places.

Foul in the buildup

No other game has been changed as much by video replays than soccer. The English Premier League introduced the video assistant referee (VAR) in 2019, and it took exactly one weekend for it to generate controversy. In a match against West Ham that August, Manchester City’s Sergio Agüero stepped up to take a penalty. City were already up 3-0—these were their years where the entire league was under the club’s oil-slicked thumb— and the Argentine striker was easy money in this position. But his attempt was a flaccid poke to the West Ham keeper who parried it out easily. The hometown Hammers celebrated. Being down 3 goals is brutal; being down 4 is embarrassing.

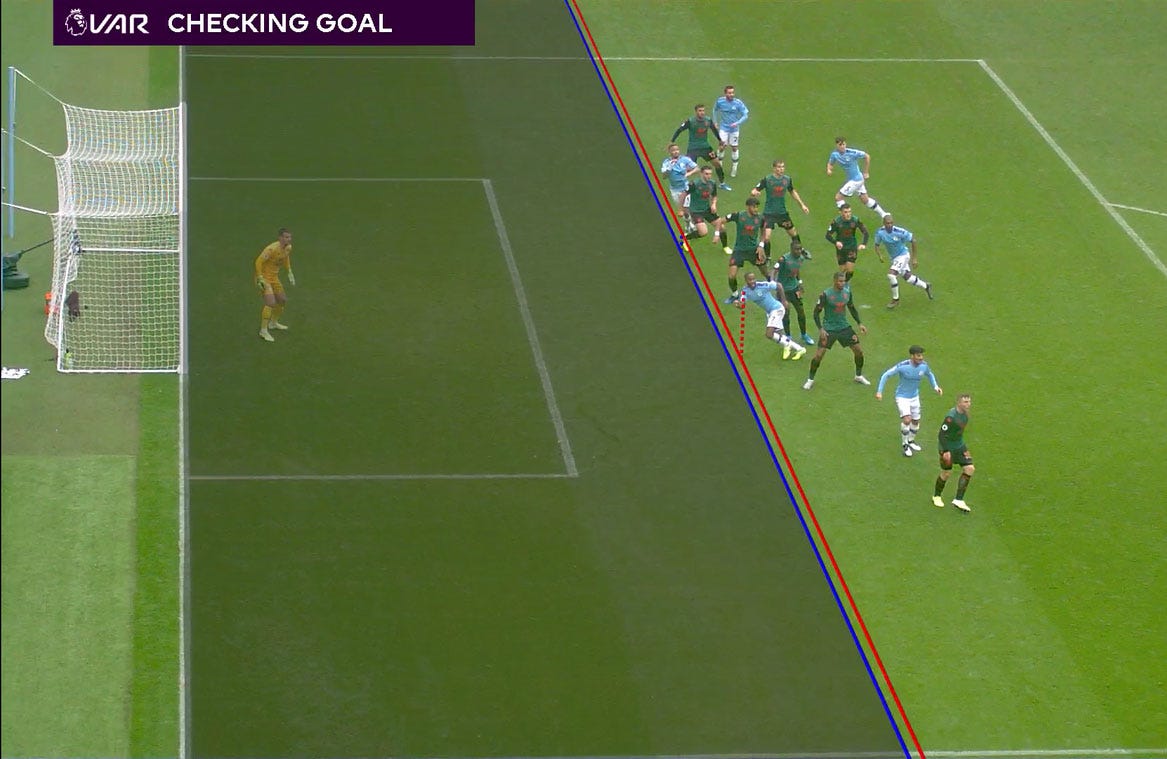

And then it was like all the joyful air in the stadium got sucked out through one of the stadium’s digital display boards when it flashed a message that would become increasingly ominous and annoying in years to come: ‘Checking Goal.’ Depending on who you ask, either one of the West Ham defenders had drifted into the penalty box a flash of a second too early or the West Ham keeper left his line before Agüero’s foot made contact with the ball or both happened simultaneously. Regardless, the VAR alerted the on-field ref that something was amiss and, after a review, they did the whole thing again. Agüero slotted it home. He was never going to miss twice.

The controversies haven’t stopped since then. Fans are frustrated both by the arbitrariness of individual decisions as well as the impact that VAR has on the sport as a whole. Goals seem to be celebrated on tape delay because players often don’t know whether some minute infraction will have to be investigated before they put a new number up on the scoreboard. Even the binary infractions—like offsides—that VAR seems perfectly suited for have driven people halfway insane. There’s a jurisprudential air to the entire conversation. Does a fingernail being on the wrong side of a defender constitute an advantage? How does a referee reconcile the real-time and the slow-mo? Are rules meant to be enforced objectively or subjectively?

Fans have started to revolt. Norwegian fans recently protested VAR by throwing fish cakes and croissants on the field during matches. (Apparently they wanted to attract a swarm of seagulls and cause some on-pitch chaos.) Sweden’s top league—where, naturally, clubs are required to be majority-owned by fans—has refused to implement VAR at all, with fans claiming that it would buff out the human flaws from the game that make it so beloved.

Clear and distinct errors

What is the cost of being correct? There’s a strong argument to be made that fairness is the holy core of sports, and that ill-gotten gains hollow out that liturgy with doubt. But what of Diego Maradonna, who in lifting his stubby arms to God and basically spiked a damn soccer ball into the net against England in 1986 gave us a World Memory, a collective experience that is immediately intelligible no matter where you are. Is it too romantic to think that the fair outcome in that scenario would have been something less vital? Is being right really the only thing that matters?

Review delays like the one in the Cowboys game are irritating but commonplace in modern sports. The NBA had more than 2000 instant replay reviews last season—about 2 per game—while the NFL had around 300, each one lasting an average of two-and-a-half minutes. Fans have begrudgingly gotten used to them, and players have even started proactively advocating for reviews to be initiated. One of the funniest developments in the NBA over the last five years has been watching players called for a foul spastically swirl their fingers like they’re spinning an invisible pizza to signal that they want their team to roll the tape and challenge the call. It’s sort of a space age evolution of what we all grew up doing at pick up games when we wished there was some sort of irrefutable way to call bullshit on someone who complained about a phantom foul.

But the ubiquity of replays in sports are also a scale model for the wider superimposition of technocratic solutions that dominate modern life. We’re told that technology will solve all of our problems if only we let it take the wheel. That hasn’t exactly worked out: the algorithms that promised to make financial processes like mortgage applications less prejudicial have only reinforced prior biases, and the AI that promised to do away with mundane tasks has been put to work filling the internet with uncanny slop. In sports, we were told that these cameras will fix things, this technology will level the playing field. But as anyone who has spent hours reviewing the Zapruder film can tell you: just because you caught it on camera doesn’t mean you’re any closer to the truth.

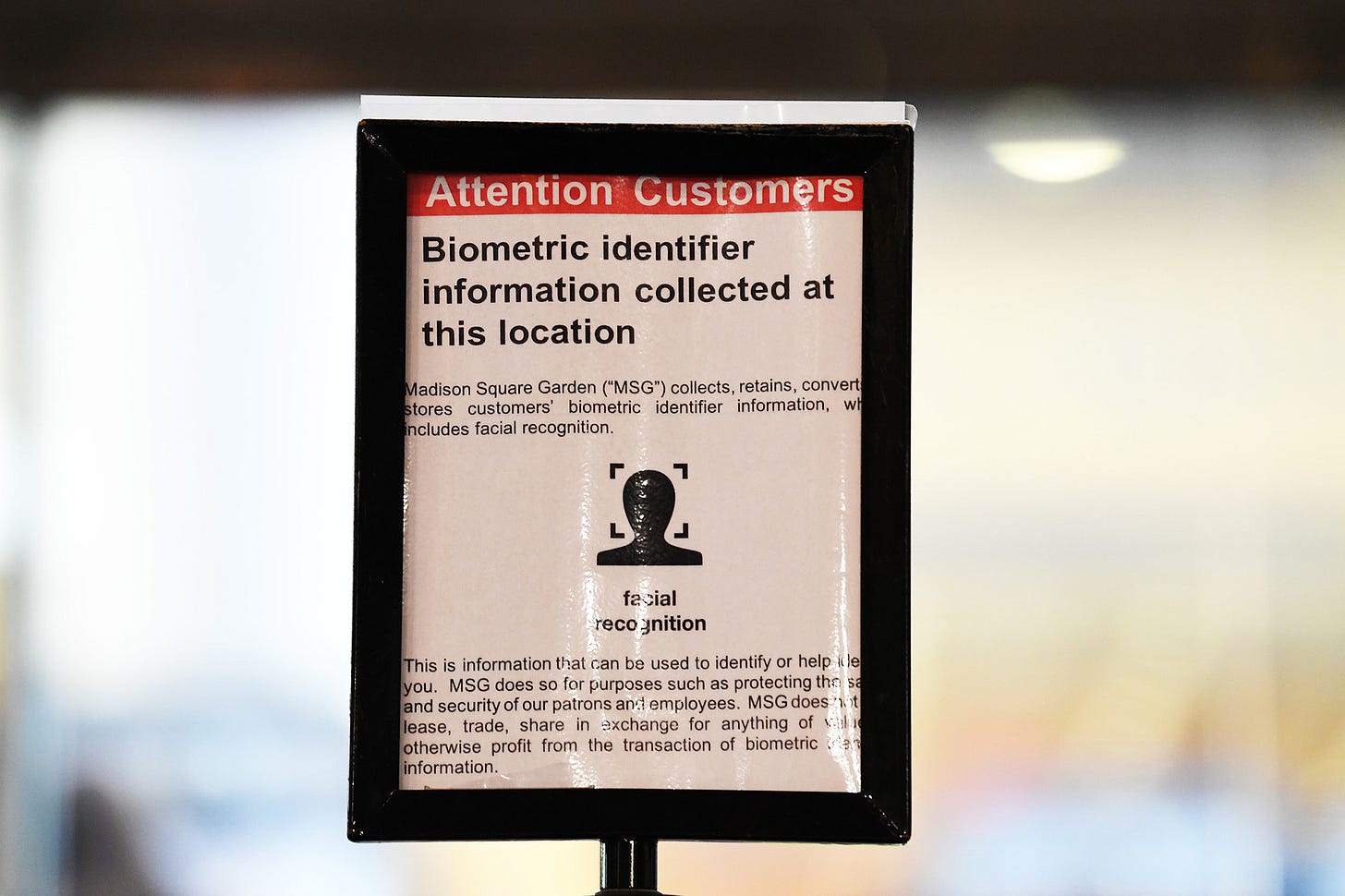

The ubiquity of cameras in stadiums—from the artillery-like broadcast rigs that surveil sidelines to the fizzing SkyCams that drop in and out of sight on a string like a cycloptic spider—has led us to strange places. It’s hard not to think of the fortressed surveillance state when you see the phalanx of cameras documenting every movement on the court or field, but those eyes are also watching you. Knicks owner and perennial contender for Worst New Yorker James Dolan enthusiastically equipped Madison Square Garden with facial recognition cameras and has used it exclusively to carry out personal vendettas like some mundane Bond villain. In November 2022, a lawyer named Alexis Manjano was accosted by MSG security when he was on his way to his seat to watch the Knicks play the Celtics. It turned out that the firm Manjano worked for was suing Dolan on behalf of a fan who fell out of a box during a Billy Joel concert, and the facial recognition software had been trained on the headshots from the websites of firms that had pending litigation against MSG Entertainment. It made no difference that Manjano wasn’t working on the case or that Dolan’s company was being sued by several dozen law firms at any given moment. Manjano was escorted out of the building.

It wouldn’t be the only person to get tossed out of an event in a venue owned by Dolan—another lawyer got caught in the dragnet while he was heading to his seats at a Rangers game at the Garden—nor the only stadium to use facial recognition technology. The NFL stadiums in Atlanta, New Orleans, Miami, and Cleveland use them, as does the New York Mets’ home diamond Citi Field.

The rationale is a familiar one in the conversation around surveillance: trade your privacy for convenience. “Your face is your ticket,” says the tagline for the event technology company Wicket, who works with football teams like the Carolina Panthers and MLS team Columbus Crew. The stress from handing someone a piece of paper might have been giving everyone carpal tunnel, I don’t know, but the compromise seems a disproportionate one. People get to save a few seconds on line at a concession stand or a playoff game, and a private company gets a library of millions of faces to share with police departments or ICE.

But then, the replay camera has seeped into other parts of modern life too. We trust less and less of what we see and some are driven to obsessive analysis as a way of digging for the actual truth. We watch replays constantly—the analyze whether Luigi Mangione was a professional or an amateur; the blood splatter patterns from Trump’s clipped ear; the shape and velocity of apparent UFOs—waiting for the real answer to unveil itself, and I think we do it because we’re driven bonkers by both the sheer amount of chaos and misery in the world.

“After the earthquake in San Francisco, they showed one house burning, over and over, so that your TV set became a kind of instrument of apocalypse,” Don DeLillo once said in an interview. “This happens repeatedly in those endless videotapes that come to life of a bank robbery, or a shooting, or a beating. They repeat, and it’s as though they’re speeding up time in some way.”

For me, it feels less like an accelerating timeline than a flash flood as we drown in information that doesn’t really tell us anything. The same few frames of a replay gets shown to us over and over again and then a referee emerges to tell us that, actually, no, that it wasn’t a catch or a foul or a first down. Your eyes have deceived you, and none of your groaning or complaining or fish-cake throwing can change that.